Psychedelics have a long and tumultuous history. They’ve been used in religious and cultural ceremonies for over a thousand years but really grabbed public attention in the counterculture movement in the 1960s.

People have been divided ever since, between an enthusiastic acceptance of probing the psyche with mind-altering chemicals, and a fear that such experience can only damage the individual or cause society itself to unravel as its members all lose their minds.

There does exist a more moderate and open-minded view of both the potential benefits and drawbacks of these substances. While the law and social stigma have made it difficult, research into psychedelics has been growing, and unearthing many interesting effects on our bodies and minds.

So far there does appear to be a number of profound benefits to going on a ‘trip’ – provided the right precautions are taken. Psychedelics have shown promise in alleviating depression and anxiety, and helping terminal cancer patients deal with a fear of dying, for instance.

But they’re also proving to be valuable tools to help elucidate the nature of mind and consciousness, to study how the brain works, and to figure out where and how our perception of the world is formed. That’s what we’ll explore here.

The Language of the Brain

The brain, when it is functioning normally, relies on different systems and neural pathways communicating with each other in a consistent and hierarchical fashion.

There are many levels of detail to this communication, from the types of neurons and the varieties of chemicals they use as messengers, up to the large structures that contain millions if not billions of neurons and play important roles in things like language, vision, emotion, and memory.

These larger structures themselves make up networks that help coordinate thought and behaviour. One of the most prominent is the default mode network (DMN), so-called because it is found to be most active when we’re not solving tasks or attending to the outside world.

The DMN appears when we’re somewhere in our own heads, daydreaming, thinking of the future, and talking silently to ourselves. It goes quiet when we need to pay attention to something in our environment.

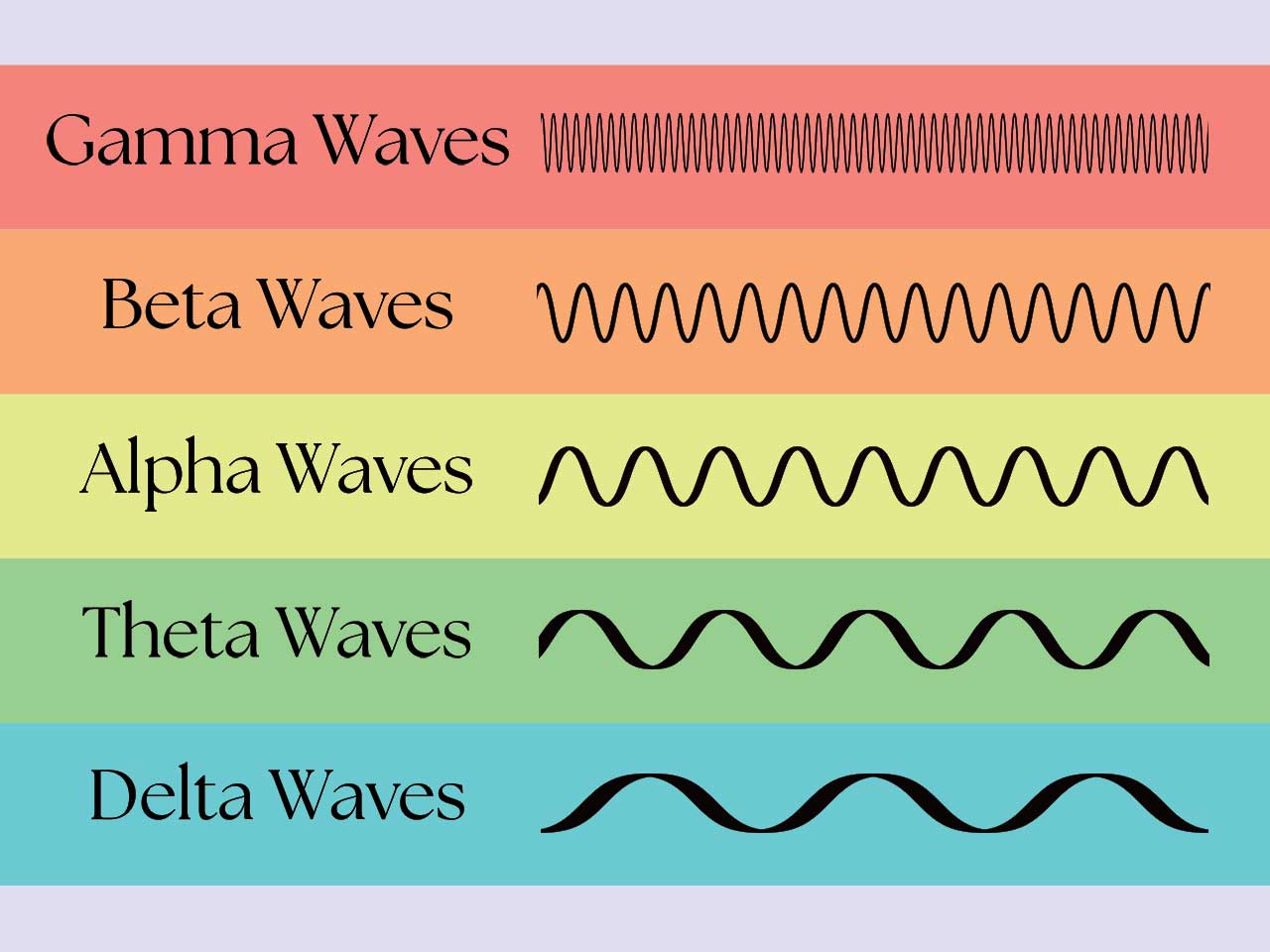

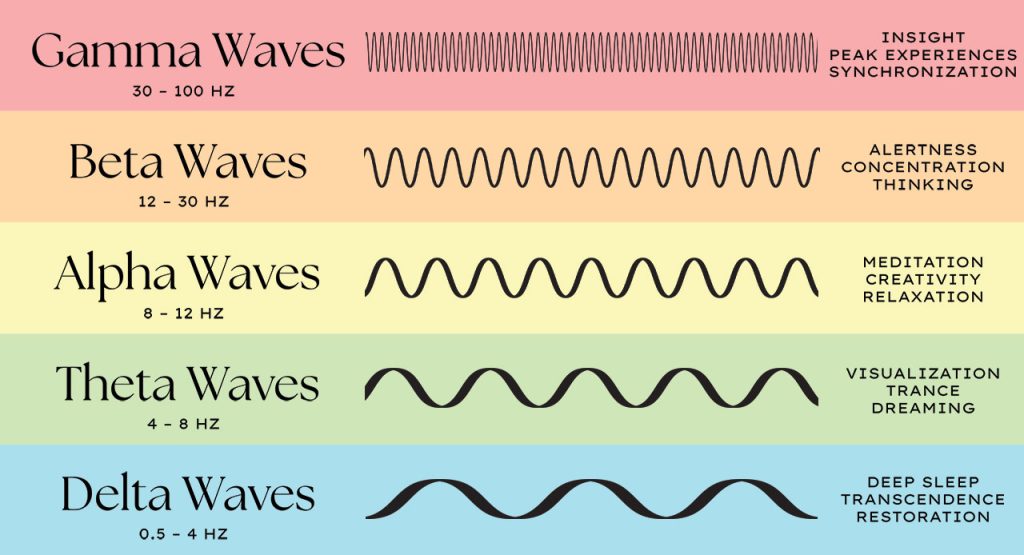

One of the more interesting discoveries regarding the ways all of these mechanisms operate is the prevalence of brain waves. The activity of the brain relies on oscillations of different frequencies to achieve communication.

They are slow when we’re asleep, moderate when we’re awake but restful, and heightened when we’re alert and engaged in a task.

When it comes to psychedelics, their effects can be seen everywhere—deep down in the tiny details all the way up to the global dynamics. They mess with everything.

Altered States of Consciousness

The classic psychedelics—LSD, DMT (the active ingredient in ayahuasca), and psilocybin (in magic mushrooms)—all act on the 5-HT2A receptor in the brain’s neural pathways.

This is a serotonin receptor, and it’s predominantly found in regions responsible for learning and cognition. When rats have these receptors blocked, they become inflexible and unable to adapt to a changing environment.

But when psychedelics bind to 5-HT2A receptors, the opposite happens—all the rigidness, the mental models that guide our understanding of the world and allow us to make decisions, they’re relaxed. “All of these higher-level constructs have been dissolved,” says researcher Karl Friston

Relatedly, under psychedelics, the default mode network shows decreased activity, suggesting that the inner voice and seat of the self-reflective ego has released its grip. There is a decrease in most frequency bands, particularly alpha, and an increase in signal diversity.

There have been several attempts to measure and quantify the complexity and orderliness of brain activity. One study using Lempel-Ziv complexity found that brain waves on psychedelics are more disordered, while another using Granger causality showed decreased functional connectivity.

A 2011 study of brain waves on DMT agreed that there was an overall decrease in most frequencies, but saw an increase in global gamma coherence during peak psychedelic experiences, something they note is also prevalent in deep meditative states.

With our sense of self and higher cognitive faculties on the recline, all that structure and organization the brain usually relies on gives way, areas of the brain that wouldn’t normally talk to each other start collaborating, and hallucinations ensue.

The Predictive Brain

One of the leading theories of how the brain works is called ‘predictive processing’ or ‘predictive coding.’ It posits that the brain is not a passive consumer of sensory signals, but that it’s constantly making predictions about what the causes of those signals are.

We can see this when we have two very different interpretations of the same input—when you could see a vase or two faces, but not both at the same time. Or the well-known dress that took the internet by storm, how can we all see different colours when we’re looking at the same thing?

If you look at one of the mind-bending visual illusions that seem to move when you know they’re not, predictive processing would suggest that what you’re seeing is the prediction itself, what your brain is expecting to see given the knowledge and information it has. The image has tricked your brain.

The theory relies strongly on the hierarchical nature of the brain. There are high-level structures that make predictions and send them down, where they meet the incoming sensory information that arrived at the lower levels.

When the sensory signal doesn’t match the predictions coming from above, an error signal is sent back up the hierarchy, so the mental model can be updated and new predictions formed. Those who subscribe to this theory often call our perception of reality a “controlled hallucination.”

“The entirety of perceptual experience is a neuronal fantasy that remains yoked to the world through a continuous making and remaking of perceptual best guesses, of controlled hallucinations,” says neuroscientist Anil Seth. “You could even say that we’re all hallucinating all the time. It’s just that when we agree about our hallucinations, that’s what we call reality.”

Under the influence of psychedelics, the control is given up.

Karl Friston and Robin Carhart-Harris defined a model called REBUS, for “relaxed beliefs under psychedelics.” On these drugs, the brain is no longer relying on prior beliefs and learned concepts about the world and its workings—it’s an uncontrolled hallucination.

Riding the Wave

There is growing support for the predictive processing model of the brain, and some of it comes from the research on psychedelics.

Katrin Preller ran a study in 2018 that found brain waves on LSD shows enhanced connectivity among lower-level brain regions responsible for sensory input processing, and reduced connectivity among those responsible for higher-level concepts and interpretation of sensory information.

Preller published another study in 2019, this one showed that information flowing up the hierarchy from the thalamus to cortical areas was increased, while information flowing in the opposite direction decreased.

These help explain why we have heightened sensory experiences—there’s increased sensory information flowing up the hierarchy, without the subsequent predictions and mental models there to constrain and interpret them. We’re just awash in colours and sounds and sensations.

Another interesting insight started with a paper by the computational neuroscientist Andrea Alamia and his team.

They made a simple model of predictive coding, highlighting two important components: the time it takes a prediction or error to travel between levels of the hierarchy, and the time it takes for a group of neurons to return to baseline after the signal stops.

As the model made predictions and updated in response to errors, it produced waves of signals with a frequency of about 10 hertz—alpha waves.

Perhaps the brain waves we see in people represent the rapid push and pull of predictions and errors across the brain as it makes sense of reality. The more engaged and alert we are, the more work our brain does to update itself and the higher frequency waves we see.

The finding piqued the interest of Carhart-Harris, who sent Alamia’s team data of brain waves on DMT, and they found that the waves started going in the opposite direction. “The drug goes in … and the waves just shift,” said Carhart-Harris.

Finding Signal in the Noise

People can have profoundly life-changing experiences with psychedelics. If the predictive brain hypothesis is correct it might hint at one reason why.

It is all too easy for us to get stuck in negative loops of self-doubt, rumination, and regret. We get set in our ways as we get older, mental habits form and it gets more difficult for us to change our perspectives.

This is another way of saying that we become a little too reliant on the mental models and prior beliefs we’ve built up over time.

There are often many ways of looking at things—if we focus on the bad events, on our flaws, on the worst future possibilities, we’ll get stuck with this interpretation. Our predictive brain will start seeing and expecting the negative in everything.

Famous psychonaut Timothy Leary called psychedelics a “chemical key” that “frees the nervous system of its ordinary patterns and structures.”

Psychedelics can give us a much-needed shake-up. Suddenly those stubborn models are broken loose, the top-down control is released, the ego dissolved.

Now all those brain waves are flowing in the opposite direction, and strange, wonderful, vibrant new perspectives and ideas can flow in from the other end.

Many of them may be nonsensical, but others might establish themselves as deeply felt truths—it is common for people to feel a part of nature in a way they hadn’t before, a view that lingers long after the psychedelics have worn off.

Sometimes our ‘controlled hallucination’ —what we think of as real—isn’t the right way to see things. Counterintuitively, ‘losing your mind’ for a time can help you see more clearly.